For the past fifteen years, the Peruvian economy has been booming; since the start of the last decade, the country has experienced a healthy dose of GDP growth, which has more than doubled since 2000, coming from a little more than 50 billion US Dollars in that year, to 200 billion US Dollars in 2014 (Fig. 1), representing an average growth of 7.8% each year in that period.

A similar trend is seen in the GDP per capita (PPP); a well-known but inexact measure of living standards within countries. According to The World Bank, in the year 2000, GDP per capita in Peru was over 5100 US Dollars, but by 2014 that figure had risen to over 12,000 US Dollars. This is the Peruvian miracle; an unexpected and very important economic growth at a time when almost all the developed world was in crisis.

The causes for this rise are mainly explained by foreign, as opposed to internal, factors. In 2000 Peru was shocked by a corruption scandal that reached the top spheres of central government and saw the then President Fujimori flee the country to try to resign by fax from Japan before being removed from office by the Congress on the grounds of moral incapacity. He is now in jail, sentenced on corruption charges and for violation of human rights during his presidential terms.

In that context, Peru was in no shape to carry the ‘emerging market’ slogan just yet, but the developed world was just recovering from the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the dot-com bubble four years later after the 9/11 attacks occurred in United States of America. This is related to Peru because in a world in crisis, investors no longer saw the dollar as a safe haven and instead retreated to commodities such as gold and silver, among others, and Peru was a top destination for this type of investment.

Gold prices rose fivefold, from 300 USD/oz in 2001 to more than 1800 USD/oz in 2011 and silver rose from less than 10 USD/oz to more than 50 USD/oz in the same period. The prosperity in commodities prices and an unstable world led to this Peruvian miracle that it is now studied and praised by many; even COFACE and Bloomberg have called Peru one of the new ‘hot emerging markets’ for the near future.

However, there is a problem: commodities are no longer hot investments. Their prices are gradually declining and the developed world is slowly returning to the path of growth which has led many to think that the Peru ‘miracle’ is almost certainly over and Peru will return to modest rates of economic growth this year as predicted by the International Monetary Fund. But what if we look beyond the GDP in Peru? What has this growth left for the country?

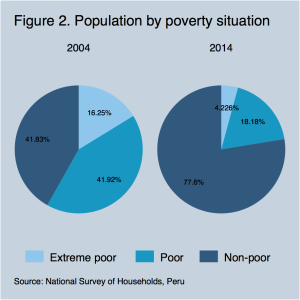

Figure 2 shows the poverty situation of Peruvian population from 2004 to 2014, using the oldest official and comparable statistics in poverty for Peru (it is safe to assume that the situation was even worse in the 1990s).

In 2004, more than half the population in Peru was living in poverty or extreme poverty and roughly 40% was non-poor. Ten years of strong economic growth has certainly improved the poverty situation in Peru; the percentage of non-poor people almost doubled and meanwhile the total poor population has gone from 58% to just over 22% last year, an important reduction that signals a positive trend in living conditions.

A sound macroeconomic management by central government was able to carry and maintain this growth during a long period of time; The World Economic Forum ranked Peru 21 out of 144 surveyed countries in macroeconomic environment in its latest Global Competitiveness Report, thanks to its balanced budget, low inflation prospects and low government debt.

Whilst this all sounds like good news, upon closer inspection there is still one problem: The Peruvian population is not living particularly better now and most of it – more than 8 out 10 Peruvians – are still living at the bottom of socioeconomic classes. This means that a large percentage of population considered non-poor is still within the poverty threshold or at risk of becoming poor soon. GDP growth has improved the economic situation in Peru but the country is still far from becoming a developed society, or even ensuring that its population lives with better standards.

Peru is at a crossroads: it is still considered one of Latin America’s stars but it is currently experiencing constant political instability created by corruption, particular interests and failed promises by its governments – the last three elected presidents are either in jail or under investigation on corruption charges – which is already affecting growth prospects and will continue to do so. But more importantly it will affect the kind of lives people are able to live in Peru; many economic reforms are needed in the country, but political and social reforms are even more crucial in securing long term growth and ultimately a better-off Peruvian population.

Author Biography

Pedro Mario Portocarrero Moreno is a Peruvian Economist, with a broad perspective on economic and social issues, I am currently working as professor of economics at a university in Peru but soon will be a Social Policy master’s student at The London School of Economics and Political Science. My main interests are development studies, policy implementation, politics and economics.