[In this article, guest contributor Piotr Kuzniatsou takes a look on the use and successes of social media for the promotion of civil society and describes them along his first-hand experiences in Belarus.]For a long time, civil society in general was in a state close to euphoria. The rise of social media was determined by the rapid development of the Internet, which, being beyond the control of any government, seemed to be a panacea for many ills and a versatile tool, that could give an impetus to the development of citizen activism across the globe.

Such hopes were based mainly on the notion that access to information, as well as the opportunity to speak freely for and to a large (or relatively large) audience, would solve a number of problems at once such as that of communication between citizens, self-organization, public control over the actions of the authorities, conducting outreach and information work, and more. “Receive information” and “carry information”; these two options seemed to be a magical formula to break the information ghetto, into which dictatorships and authoritarian regimes drive their people, and prevent their activation and strengthening.

A number of world events seemed to confirm these hopes and expectations. Unrest in Moldova, the revolution in Egypt, the role of social media during the “Arab Spring”, even the contribution of social networks in the “Occupy Wall Street” movement – all these and many other examples spoke in favor of the fact that now people have a new tool for collective resistance.

Today, however, taking into account the experience of the last few years, the situation does not seem so shiny and clear, at least in Belarus and in the ex-Soviet area.

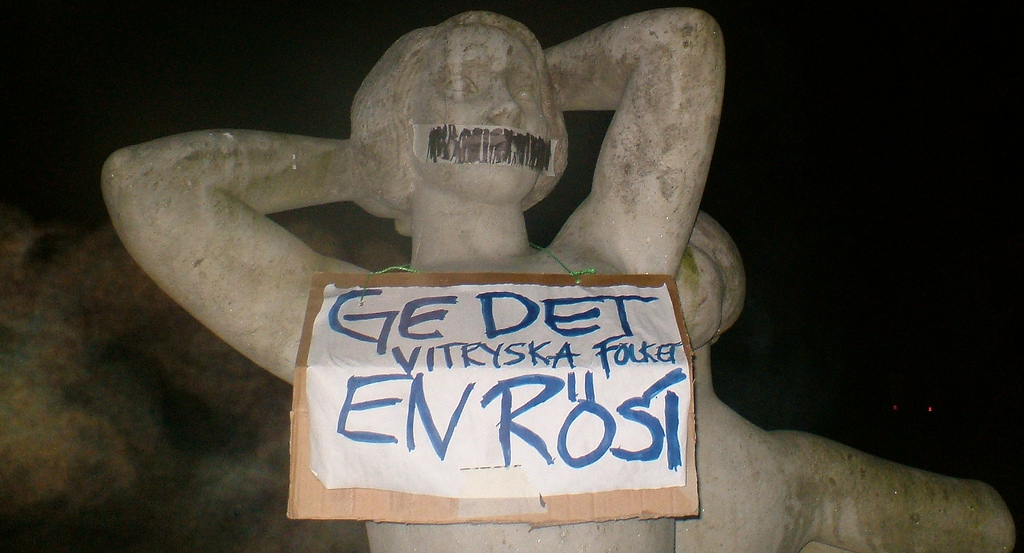

All attempts of civil activation of Belarusians in social networks collapsed, remaining non-mass and sluggish. The only exception is a burst of activity during the “silent revolution” in 2011, when young people, organized using the social network “VKontakte”, took to the streets en masse in order to remain silent and applause to express their protest against the economic crisis and “tightening of the screws” in their society. However, this case should be considered rather as an exception and will be discussed later on in this piece. In the other cases, numerous efforts of organizing seminars, training, round tables, master-classes etc. designed to equip public activists with new technologies, remained futile.

But what could be the reason for this sad state of affairs?

In many ways, the answer to this question lies on the surface. Much can be understood by a careful study of the current information war, waged by the Russian Federation against Ukraine in the social networks. The essence lies in the fact that the new technology in itself is not a panacea and not a magical formula. It is simply a tool and the formula for any societal action or change must be made up in each separate case.

This seems obvious but it is worth considering why we understand it in theory, but do not attach any importance to it in practice.

Social networks can only help develop civil society when the traditional society, which in this case is post-Soviet, atomized and has no horizontal connections, begins to understand and accept what the civil activists say in the social networks. When civil society is able to say something comprehensible and trustworthy for a majority, only then is the technical side of the question of any importance; convincing messages will be widely spread in the society, bypassing the state-controlled television.

If we do not see a burst of activity as a response to the efforts of activists in the social networks, it does not mean that the society is bad and it does not mean that the tools provided by Zuckerberg and others is not strong enough. These tools worked in Egypt and partly justified itself even in Belarus in 2011. It simply means that those who try to use the tools do not do it well enough.

Let’s return to 2011 – the only situation in the modern history of Belarus when social media helped civil society to organize itself for the challenge.

At that time, two trends were extremely strong in the Belarusian society. One of them was the strong economic crisis, which affected virtually everyone as three-time devaluation of the national currency caused a considerable drop in living standards. The second trend came after the brutal end of the presidential elections of 2010, which started a relative liberalization, let the majority of the population feel quite freely, be active, and finished with unprecedented repressions. Many felt disappointment, impotent anger and depression.

The offer of “silent protests” had its time and place. On the one hand, it gave people the opportunity to express their attitude to what was happening in the country. On the other hand, the form itself – to go out and keep quiet, without any violations – inspired hopes that this one time the authorities would not be able to find opportunities for repression and suppression. That is, the attractive formula of behavior suggested in the right moment, when the protest activity of the society was at a high stage, led to the desired result: people went out into the streets.

Another example is the current information confrontation between Russia and Ukraine. Russia, conducting a campaign of outright disinformation and “black” propaganda, made a bet on a clear and long-known mental imprint of the total population of the former Soviet Union: fear and hatred of fascism. Seeking to provoke rejection of the Ukrainian events, Russian PR first of all, without going into details, called the Ukrainians “fascists” and very quickly achieved the desired effect. “Mental imprints” reside in everyone, and when activated can instantly become topics that people hear and believe in.

In both cases, the success of information work was determined by the fact that necessary and desired information was spread in the right way, time and place. Russian propaganda operates through all possible channels of communication (equally through TV and social networks), as Russian resources allow it, but in case of the “silent revolution” social media was enough; the necessary message at the necessary moment was immediately perceived by the people and disseminated further by them.

These examples are only a small part of a large number of situations that can be carefully studied on how to successfully use social networks in public activities. But detailed analysis of any of these situations will lead to only one conclusion: at its core, social media differs only from any other method of disseminating information by the greater extent of inclusivity of the end user. They have endless opportunities for generating one’s own or responding to someone else’s content by comments and “likes”. However, despite all this, social networks remain simply a tool for disseminating information and the implementation of information campaigns; the result of these campaigns will always depend upon the quality of disseminated information and upon the successful campaign planning.

But what does this mean in practical terms for Belarusian civil society, for partner and donor organizations working with Belarusian NGOs?

It means that, for maximum effect, it is necessary to redesign many of the activities related to the introduction of new technologies. It is necessary to minimize the number of seminars and training on getting acquainted with social networks. Today social networks are so simple that almost anyone can get acquainted with them with minimal help. Moreover, everyone who needs it has most likely found help already. Instead of focusing on promotion of only the technical side, it is necessary to pay attention to the following areas:

1) Investment in special studies aimed at the identification of the most pressing topics for the broader public, the most wide-spread “mental imprints” and selection of the most suitable strategy for the information work of NGOs from them;

2) Investments into professional development of marketing campaigns for NGOs, information campaigns, clever high-quality messages based on the expectations of citizens and on professional “smart” presentation styles.

With the results of such research in hand and with the opportunity to order such analytics, mature and interested non-governmental organizations will have the opportunity to plan and, most importantly, successfully implement information, marketing, protest or public campaigns. This will mean a transition to a whole new stage of development of information work for the Belarusian public sector.

Author Biography

Piotr Kuzniatsou is a Belarusian civic and media activist from Gomel. He is the Head of the Board of Establishment “Center of Regional Development GDF”, founder of the most popular Gomel regional independent on-line newspaper “Strong News” and analyst for the regional think tank “Strategic Thought”.

You can also find him on Twitter (en), (ru), and Facebook

*Pictures by Virre Livendil Annergard and KP M