Voices from the Past, Lessons for the Future – Conclusions (Part I)

Two hundred years ago, the last shots of the guns at Waterloo marked the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the dawn of a Century that would experience the changes catalysed by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. But those very same shots also marked the beginning of a path that would lead the world to face another conflict within the next one hundred years. It was those events, elements, decisions and policies that became the roots and origins of the First World War.

Revisiting a Century

Structural factors played an important role in paving the way towards war and those were pointed out throughout the series, but it is noteworthy to remind them. The ideals set by the French Revolution, including those ideas of freedom, national consciousness and identity are the main and most important factors, following Segesser (2013). The impact of those ideas had, of course, varying degrees depending on the country or faction referring to them, especially in the Great Powers with a multi-ethnical composition, such as Austria or Russia. Those elements were the ideological inspiration for the assassin of the Archduke, for example, or for those groups and minorities that were striving for independence or to join other nations where they would be part of the majority. Following the 1848 revolution, this trend also affected Germany, which at the time was divided into principalities and small states and was the main area of contest between Austria and Prussia: simply put, it laid the groundwork for the German unification in 1871, which alone was another important factor for the political climate of its time due to its impact on the balance of power.

The victories at Trafalgar and during the Napoleonic Wars brought the British Empire a naval and international supremacy, which had multiple effects for both the Empire and the international system. The first was that such supremacy became of capital importance as the main tool to protect the British Isles and the Imperial interests, as well as to exert its power while saving the huge expenses of sustaining a great army, as Kennedy (2004) points out. This is the reason why the naval race and colonial competitions – waged by France and Germany, and to a lesser degree: Russia – were both a sources of concern for the Empire, since one of its main priorities was the protection of both.

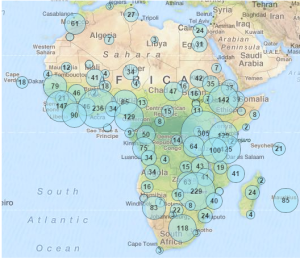

The advent of the Industrial Revolution and its effects as well meant, as Kennedy (2004) explains, changes in the composition of certain military assets – like ironclad warships, machine guns and artillery, among others – that facilitated the European penetration of other areas of the world like Africa or Asia, and in doing so: new means to consolidate the dominion over the far-flung territories already under control[1]. But as it happened, the combination of Industrial Revolution and the new Colonization brought a new set of competences to the Great Powers, which would reach its climax with the Great War. In addition, the Industrial Revolution both enhanced and eroded the British supremacy, since the other great powers also had access to the new technologies and could modify or modernize their military assets, thus gaining the capacities to actively compete with the Empire.

This competition led also to the establishment of alliances and their strengthening. But this part will be discussed later on, simply because in the aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo and until the Crimean War, there was a certain objective in common that even France (defeated in the Napoleonic Wars) and the German Empire could agree upon: to preserve the equilibrium and the status quo, in order to avoid the clashes that took place not only with Napoleon but also with Louis XIV. Similarly, this brought another couple of elements into play that, combined, proved to be catastrophic by the earlier days of the 20th century, and even on the eve of the Great War. The fact that there was a certain degree of stability thanks to the Concert of Nations, along with the mutual integration of economies through trade as another mechanism to ensure stability, led to a generalised idea that the resulting economic interdependence would make the Great Power leaders resort to reason and avoid any confrontation (Kennedy, 2004). Ideas that were broadly accepted and taked for granted especially in the British Empire. Unfortunately, these two factors led to the British having an army only for colonial services while it was not prepared to face a considerable war in Europe. Nor was it willing to intervene actively in European affairs until the ‘German Challenge’ became a strategic concern.

More than the French ambitions against the British interests, it was France’s ambitions towards Germany and later its desire to revenge its defeat in 1870 what contributed to a significant erosion of the European equilibrium, although France was not alone in doing so. Germany, for instance, shattered the status quo right after Emperor Wilhelm II assumed the foreign policy of the country. Chancellor von Bismarck had acted as one of the Guardians of European equilibrium along with the weakening Austrian Empire – a useful tool for diplomats to hold other powers’ ambitions at bay[2]. Indeed, the von Bismarck, dubbed the Iron Chancellor, was conscious of the impact the unification and the rise of the German Empire would have on the European equilibrium. For instance, Austria was the first affected great power but not the only one: Great Britain similarly began to see a strong Germany as another potential continental hegemon. France was traditionally one of the main powers affected by the German consolidation and rise, preparing the war plans to recover the lost territories following its defeat in 1870. Russia in turn did not welcome the German ascent since it meant a more independent Germany from Russia’s will. However, it still sought German help when it came to obtain support for its interests.

Many blame von Bismarck’s system of alliances as one of the main causes for the war, but this statement might not hold true after all. The system clearly worked while he was on post and even managed to keep the equilibrium in Europe by mainly estabishing alliances and agreements with Russia and Austria, at the point making Berlin a hub for diplomacy (Kennedy, 2004, Morgenthau, 2008). Following his departure, Kaiser Wilhelm II’s policies did not bode as well with the delicate system as the more planned actions of von Bismarck had before: the non-renewal of the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia only meant that now France would end finding a key ally to materialize its purposes while Germany would end losing an ally and security on its eastern border[3]. Additionally, the naval race against the British Empire and the quest for colonies while protesting the agreements of the 1884 Berlin Conference regarding the repartition of Africa, led to another major breach of the precarious equilibrium of the years following von Bismarck’s retirement and further endangered the position of Germany[4].

Austria came into the equation again with its first annexations in the Balkans, colliding with the interests of the Ottoman Empire – which was a waning one – and of Russia. Those actions made by Austria would ignite the Austrian Empire’s inner tensions, the clashes with Serbia and its main ally, Russia, as well as the Balkan Wars that took place right before the outbreak of wider scale war. But also, Russia had an impact on the Balkan stability after forging a series of local alliances for the sake of its own interests and directly encouraging the Balkan countries to collide during the afore-mentioned wars. Generally speaking, the alliance between Germany and Austria would place the former on a collision course with Russia, an event of which France would take full advantage. Paradoxically, it was still an important element of stability to check the surrounding powers’ ambitions, given its geographical and strategic location. But as Kennedy (2004) describes, its inner tensions, the clashes with Russia and its ongoing decadence, would be important elements for its eventual downfall and a war could be the only result.

Not only the Kings upon their Thrones

But again, the blame cannot be put only into the Emperor’s hands, or in the hands of the heads of State of the other would-be belligerents, because there were inner factors, besides the structure of the international system that paved the way to war.

In Germany, not only the unification under Bismarck’s leadership but also the political relevance and the economic growth stimulated a sense of pride and enthusiasm in the country’s people, not to say nationalism. For example, as Kennedy (2004) remarks, some nationalist organizations welcomed the Kaiser’s efforts to increase the German influence in Europe and beyond along with the founding of more colonies, as well as encouraging the government to do so[5]. This proved to be a dangerous combination, taking into account that not only Germany was strengthened by the wealth and the following investment in its armed forces, but also that it proved a useful political tool for the Kaiser, who in turn could have been estimulated to challenge the status quo due to the increased growth (Barth, 2012; Kennedy, 2004). The foreign policy implemented by the Kaiser aided him to win the sympathies of his people while at the same time it served as a feint to distract the public from the country’s inner social and political problems. In doing so, Germany had eventually backed itself into a conflict that would eventually end in war, since a confrontation with another Great Power was a needed step to take further should a crisis arise, to show that the Kaiser was ready and willing to face any adversary (Kennedy, 2004)[6].

But again, nationalism and the exploitation of the international affairs was not an exclusive phenomenon in Germany. Nor it was an entirely new factor that made other governments ponder. France, for example, experienced a clash between civilians and the military, to the point of weakening its armed forces until 1911, when again a nationalistic movement managed to unify society against Germany. This nationalistic feeling was strengthened in a similar way by the French economic growth and the colonial expansion in Africa and South East Asia, as well as the fact that France managed to weave a net of alliances with Russia and the British Empire, thus giving the government and the public enough confidence to face the Germans once again and recover lost provinces. The investments made by French businessmen in Russia additionally helped France to push Russia for an early attack against Germany’s Eastern border in exchange of further investment, a move that might be coordinated between both the government and the investors. In any case, the public support was much needed to fulfil the revenge that France had longed for since its defeat: by doing so, it sent Germany, itself and the rest of the world in a spiral downwards to the tragedy that the Great War would become.

Similarly, Russia also experimented its own wave of nationalism in a strong way, and like in Germany and France, it was widespread across people and government alike. As it was pointed out in the previous parts, the agreements signed up in Berlin after the war with the Ottoman Empire and under von Bismarck’s supervision provided the first seeds of an anti-German feeling among the nationalists and pan-Slavists. These feelings evolved later on into a more nationalistic and more militant pan-Slavism, along with traits of xenophobia, pushing Russia to further commit to its own international commitments (France and Serbia) while being at the same time victim of unrest. Such unrest consisted of social problems with workers and peasants, local revolts were a normal occurrence that involved the continuous intervention of the army against its own people, lessening the army’s moral and capabilities. Least to forget, many minorities were striving from independence.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was even worse on this regard, as it was already mentioned. There were tensions basically between the main Austrian (German) groups and others throughout the Empire: Czechs, Italians, Romanians, Hungarians (who opposed any liberalization efforts by Vienna regarding the Serbs and Croatians, as well as discriminated against the minorities present in Hungary, following Kennedy (2004)), and the aforementioned Serbs. Those tensions tended to drag other Great Powers into the Austrian inner affairs, not to say have strong clashes, as it was the case with Italy and Russia, where Italy was ready to support the Italian people living under the rule of Austria, and Russia was keen to support Serbia in the Balkans. It should be reminded the inner tensions of Austria were also a direct consequence of its earlier moves in the region.

The British Empire, in contrast, was enjoying a century of stability and hegemony, meaning that although there were social tensions and problems, those did not affect the British Empire in the same way they affected the abovementioned other Great Powers. The most pressing concerns for the British common people were for how long the British Empire would last and the relations between the Metropolis and its colonies, as well as the concerns by a certain social sector – Kennedy (2004) labels them as the ‘imperialists’ – about the survival of the Empire in terms of its decreasing productivity and the impact of such in the defence and naval industry.

But not only the international system’s structure and the inner affairs (or certain parts of the civil society) of the Great Powers had their share in crafting the way towards the Great War, and as a matter of fact, the lessons given by some previous wars were either ignored or wrongly interpreted. At such point, that the plans of war took as a basis the assumptions derived from those very same wars: interpretations that increased the confidence in reaching a certain result in no time and increasing the willingness to go into combat. Those plans, moreover, were strongly tied to the political objectives of the countries that drafted them. The role of those previous wars and the plans will be analysed in the next part of the Great War series conclusions.

_______________

[1] Additionally, the introduction of those technological elements meant that new facilities were needed to be established, such as carbon stations and bases in order to make a fleet of ships sustainable in the seas. Also, the introduction later on of submarine cables meant that the Navy needed to protect such assets as well.

[2] Russia, as Kennedy (2004) remarks, was one of the Great Powers very keen to maintain the Concert of Nations, deterring both Austria and France ambitions while evidencing it would contribute to act for the sake of other nations’ stability. The Russian intervention in Hungary is the prominent example of how Russia acted as a guardian of the equilibrium.

[3] An observation shall be made here, since the Kaiser decided not to renew the Treaty for fears of alienating Austria, a key ally in the system created by von Bismarck. See Morgenthau (2006), p. 78. Still, such move was a big strategic mistake.

[4] Lest we forget the rush for colonies following the revision of the treaty, which simply unleashed an inevitable clash with the extra-European interests of other Great Powers, the British Empire, mainly.

[5] In this case, the German elite was having similar ideas.

[6] To put it short: to demonstrate the public he indeed was the strong man he intended to show.

_________________

Sources:

Barth, R. (2012).1871 – 1919: Aufstieg und Untergang. Preußen. Die eigenwillige Supermacht. Zum 300. Geburtstag von Friedrich dem Großen. STERN Extra, 1, 86 – 97.

Kennedy, P. (2004). Auge y caida de las grandes potencias [The Rise and the Fall of the Great Powers, Ferrer Aleu, trans.]. Barcelona, Spain: Mondadori (Original work published in 1987).

Morgenthau, J. A (2006). Politics Among Nations. The Struggle for Power and Peace (Revised by Thompson K. W, & Clinton D. W. 7th Edition). New York: McGraw Hill.

Segesser, D. M (2013). Der Erste Weltkrieg in globaler Perspektive. Stuttgart, Deutschland: Marixverlag.

_________________

Image: By Author